What are closures in javascript

In my pursuit of gainful employment, I was asked an interview question about closures in javascript. The question kind of threw me for a loop because when writing javascript I have never consciously thought “ok, now I need to use a closure here.” I answered the question poorly - mostly just passing on it - and decided to research it later.

Now, I have used closures in Groovy which look something like this:

def printSum = { a, b -> print a+b }They are a common occurrence in Groovy code so I know how to use them, and I know when they are useful, but within the context of javascript, I thought it was something new I had not heard about.

If you’ve had a similar experience, and you’ve used javascript for a while, let me relieve your worried mind - you already know closures in javascript, and you likely use them all the time. It’s just a term that people are starting to use for a construct that has existed for quite a while.

Using the term ‘closure’ within javascript seems to be new, and it seems to have started because of the influx of people new to javascript, or who are coming at javascript from the perspective of another language. Anyway, the term looks as though it is here to stay, so it’s good to know what it looks like.

So this is more to explain to people who know javascript what other people mean when they ask you about closures. I am going to start small, and just build all the way up.

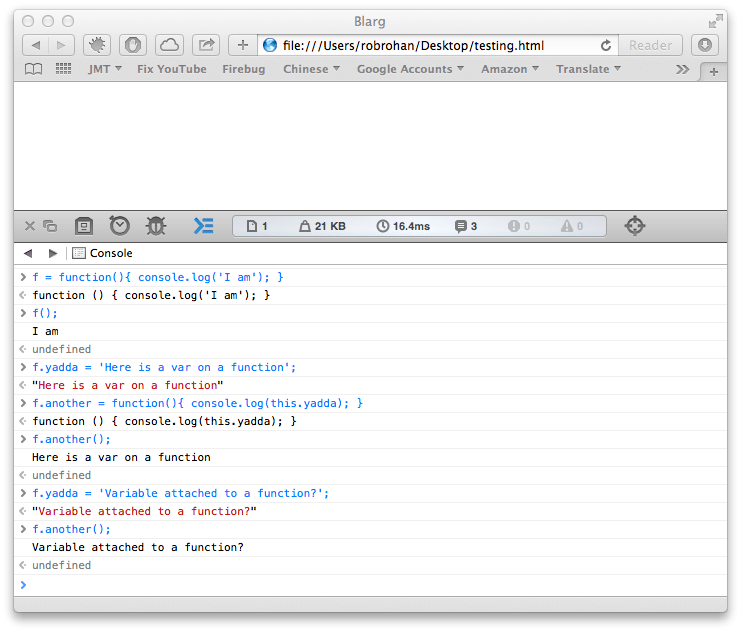

To make sure we have a common base, lets talk about this console session:

First, we create a function, f, that logs output to the console when you call it.

Next, we assign the variable yadda to the function f. Now this is part of where the confusion sets in. In a lot of languages (C, Java, etc) you can not just attach a variable to a simple function.

Then we add another function to that function that accesses the variable we set on the first function (yo dog I hear you like functions).

When we run the function attached to the first function, you can see (by the output of ‘Here is a var on a function’) that we can access the variable. And then just to prove it, we change the variable and output it again.

If you’ve done javascript for a while, all that makes perfect sense.

Now, let’s build up to what people are now calling closures. (All these examples are included in the page if you want to try them in the console)

A simple function:

var example1 = function(a) {

return ++a;

}Running example1(5) yields 6 - as you would, hopefully, expect.

var example2 = function(a) {

var b = 120;

return b + a;

}Here we’re adding in a local variable b, and running example2(5) yields 125. So what happens when we return another function instead of just a value?

var example3 = function() {

var b = 120;

return function(a) {

b += a;

return [b, a];

}

}Running example3() will return the function definition of the inner function. Calling both, for example example3()(5), will yield [125, 5].

Before we go on, I want to point out that a lot of people already build objects this way. I don’t like doing it this way for memory reasons, but something like this should look old hat to you:

var my_obj = function() {

var a = 120; // private variable

this.b = 240; // public variable

this.method1 = function() { console.log(this.b + a); } //public method

this.method2 = function() { console.log(a); }

}

var obj = new my_obj();

obj.method1();

//->360

Back to the closure example.

Since we know running the example3 function will return a new function, we can assign it to a variable and use it over and over:

var c = example3();

c(5);Basically it’s an ‘object’ (maybe class is a better way to think about it) with one unnamed method. If you noticed I’ve made example3 have one private variable that hopefully highlights the variable scope involved. If you run this over and over you’ll get:

var c = example3();

c(5);

//-> [125, 5]

c(5);

//-> [130, 5]

c(5);

//-> [135, 5]

What’s the difference between a object and a closure? The return of a single anonymous function, and the lack of a ’new’ call pretty much. Functions return functions all the time - it’s the function of a function. I went a little overboard there.

For example:

typeof example4

//-> function

typeof my_obj

//-> function

typeof new example4()

//-> object

typeof new my_obj()

//-> object

You can see how you can move around functions below. I am not even sure what you’d call the following. I’ve always called them break off functions.

var my_obj= function() {

var a = 120

this.b = 240;

this.method1 = function() { console.log(this.b + a); }

this.method2 = function() { console.log(a); }

}

var obj = new my_obj();

var c = obj.method2;

c();

//->120

Where this can look a little odd is when function short hand is used. For example:

var example4 = (function() {

var b = 120;

return function(a) {

b += a;

return [b, a];

}

})();

example4(5);

//-> [125, 5]

example4(10);

//-> [135, 10]

example4(5);

//-> [140, 5]

However, this is doing the same thing as example3, but just running the anonymous function straight away instead of assigning it to an intermediate variable.

For completeness, here is the same technique as example3 and example4, but passing in a value for the inner variable:

var example5 = (function(c) {

var b = c;

return function(a) {

b += a;

return [b, a];

}

})(10);

example5(5);

//-> [15, 5]

example5(10);

//-> [25, 10]

example5(5);

//-> [30, 5]

Hopefully this saves someone some confusion when they are asked if they know javascript closures.